Necrobiosis lipoidica is a condition that we will always have to include if we list the causes of “atypical” leg ulcers. In fact, in the EWMA document “Atypical Wounds”,which has recently been published, this entity has its section. It is not a frequent type of wound, but it is important to know it.

What is necrobiosis lipoidica?

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a granulomatous disease of unknown cause, in which degeneration of dermal collagen occurs.

The name “necrobiosis” is due to the type of alteration found when a biopsy is performed (necrobiosis = degenerated collagen). The term “lipoidica” refers to the typical yellowish colour of the lesions.

It is a rare condition, which usually develops at middle age (30-40 years). Its incidence is higher in women. Its clinical course is usually chronic.

Although it has traditionally been associated with diabetes, mainly type I, and was once called “necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum“, it seems that this relationship is not as strong as previously thought. In fact, although 50-80% of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica have diabetes, the incidence of necrobiosis lipoidica in diabetic patients is only 0.3-1.2%. In addition to showing up in healthy individuals, it has been described in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or rheumatoid arthritis. However, the relationship between these pathologies and necrobiosis lipoidica is not clear and its association may be coincidental.

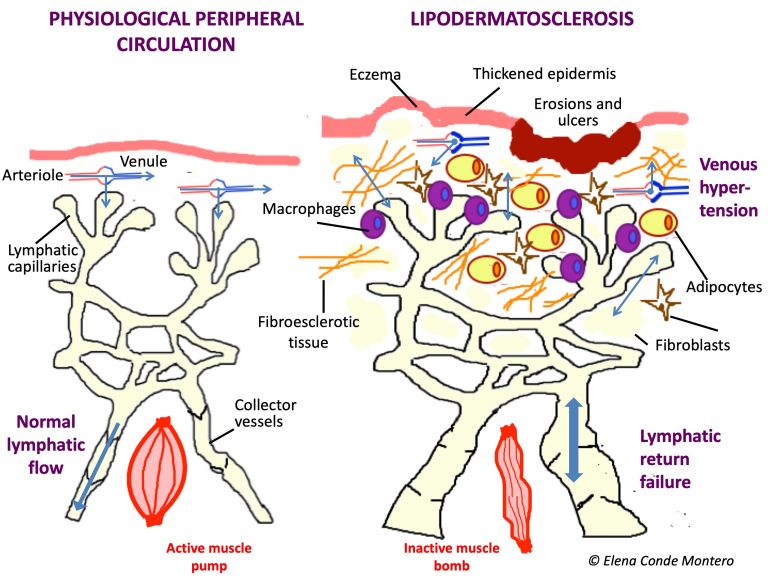

Its true cause and pathological mechanism are not very clear, but several theories have been proposed. The most accepted etiopathogeny is that collagen degeneration is due to alterations at the vascular level, by the deposit of immunocomplexes or occlusive microangiopathy. It has also been proposed that the formation of granulomas may involve a defect in the migration of neutrophils.

What about its clinical presentation and diagnosis?

Lesions usually occur in the lower extremities, especially in the pretibial region. However, specific cases have been described in other locations such as the head, trunk, genitals or upper extremities.

Although clinical presentation is quite characteristic, the appearance of the lesions varies according to the evolutionary phase of the process.

They begin as asymptomatic papules and nodules that become well-defined, yellow-brownish, with erythemato-violaceous edges and atrophic center, in which telangiectasias can be visualized.

Trauma can worsen lesions, as in pyoderma gangrenosum (patergia phenomenon).

Ulceration may occur in about one-third of cases. It should be borne in mind that chronic venous insufficiency, especially phlebolinfedema, can complicate the lesions, with greater extension and ulceration, in addition to making diagnosis difficult (ochre dermatitis may be clinically similar).

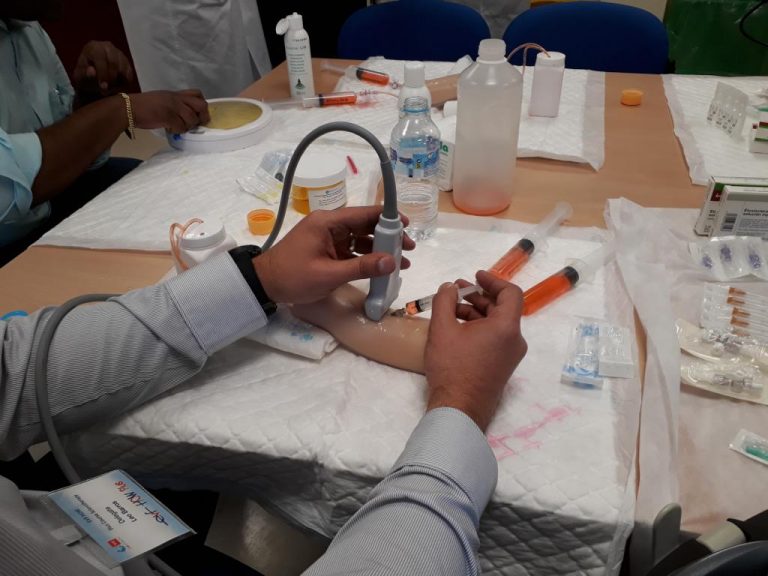

A biopsy will give us the diagnostic key. Necrobiosis lipoidica is histologically characterized by palisaded granulomas (aggregates of histiocytes and giant cells) arranged horizontally alternating with bands of degenerated collagen (necrobiosis). The wall of the dermal vessels may be thickened. The accompanying inflammatory infiltrate varies according to the time of evolution of the lesions. Initially the neutrophilic infiltrate is characteristic, which decreases when the atrophy develops.

How should necrobiosis lipoidica be treated?

The treatment of this condition is a real challenge. As there are no clinical trials to evaluate the real usefulness of the different treatments used in necrobiosis lipoidica, there are no established lines of treatment. Given that in some patients remission may be spontaneous, it is difficult to assess whether, in the published case series, the response is really due to the indicated treatment.

In diabetic patients, adequate diabetes control is essential.

The different treatment alternatives found in the literature are proposed with the potential objective of controlling granuloma formation, decreasing inflammation and/or favouring microcirculation.

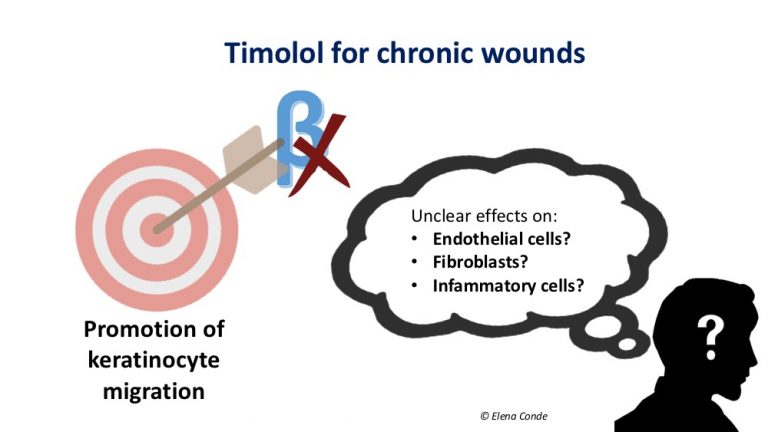

The most commonly used treatment is topical or intralesional corticosteroids, but the use of systemic corticoids, tacrolimus, pentoxifylline, phototherapy, fumaric acid esters, cyclosporine, antimalarials, biological drugs (infliximab, etanercept) is also described… In summary, a wide range of possibilities and little evidence available… In addition, many cases are resistant to the different treatments used.

What treatments can be used for ulcerated lesions?

The goal of treatment will be the same as with non-ulcerated lesions, i.e. we will also try to control the potentially triggering mechanisms. However, a strategy to promote granulation and epithelialisation of wounds should also be developed. The therapeutic challenge will therefore be even greater.

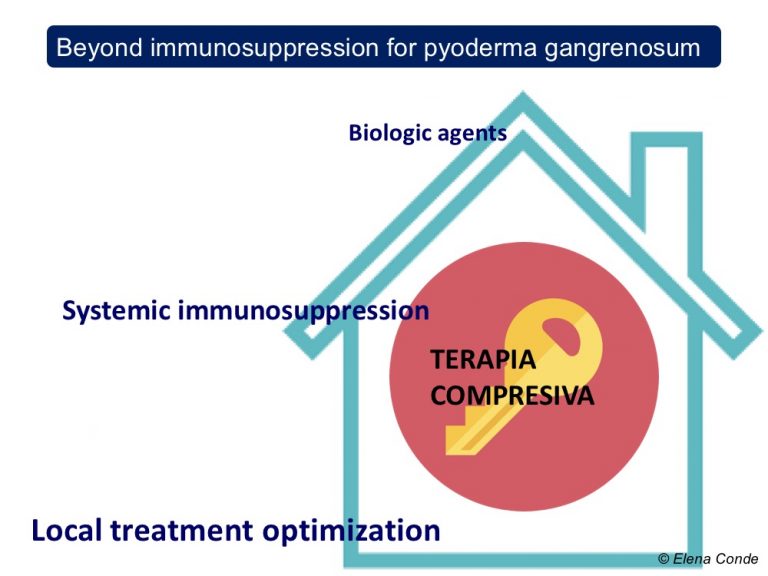

Compression therapy, as in any other leg ulcer, if there is no contraindication (always palpate pulses and perform ABI if necessary), will help healing by its anti-gravity and anti-inflammatory effect (See post Compression is key in the treatment of leg ulcers). Once the lesions have resolved, the use of compression stockings can help in the prevention of new outbreaks.

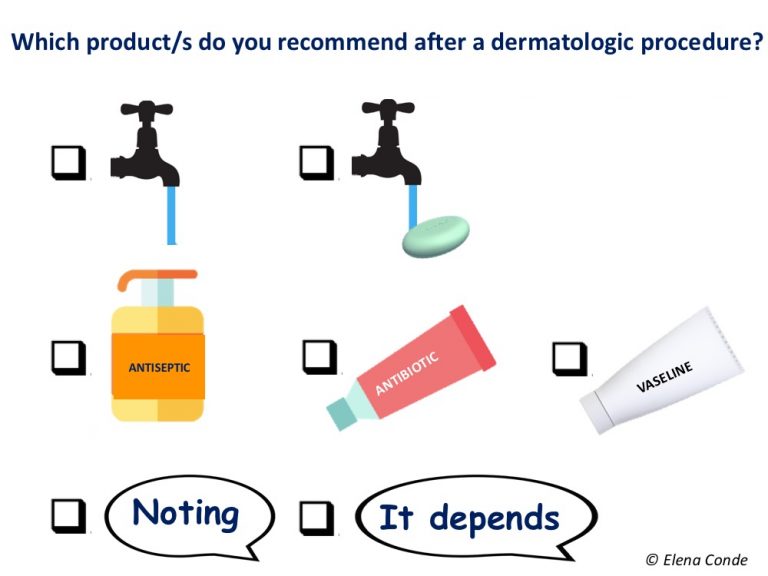

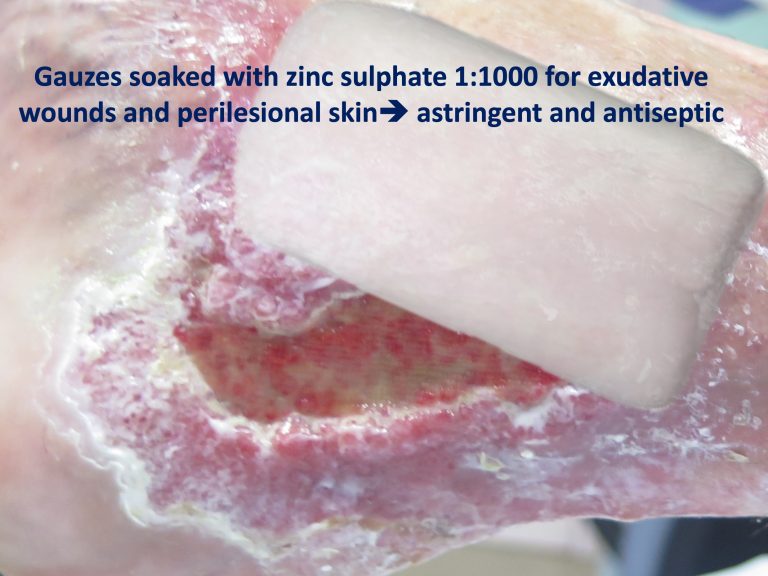

On a local level, as in any other type of wound, we will regulate the frequency of dressings and select the dressings according to the characteristics of the wound bed and edges. Skin grafting is interesting in resistant cases.

It is interesting to remember that once a correct diagnosis has been made and adequate etiological treatment has been given, which in the case of necrobiosis lipoidica is not clear, local wound care will be characterized by similar strategies to promote an anti-inflammatory environment.

What is our experience in our clinical practice?

Our experience is very limited as it is a rare type of wound. However, we have just published the excellent result, both in pain control and wound epithelization, of the combined use of topical sevoflurane (see post: Have you ever heard of the topical use of sevoflurane in wounds?) and punch grafting, in a young patient with a very painful and progressively growing ulcer. Of course, with adjuvant compressive therapy… Another alternative for treatment! ?https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31412426

2491483_1185

References:

- Isoherranen K, O’Brien JJ, Barker J, Dissemond J, Hafner J, Jemec GBE, Kamarachev J, Läuchli S, Montero EC, Nobbe S, Sunderkötter C, Velasco ML.Atypical wounds. Best clinical practice and challenges. J Wound Care. 2019 Jun 1;28(Sup6):S1-S92. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2019.28.Sup6.S1.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis Lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015 Jul;33(3):343-60.

- Marcoval J, Gómez-Armayones S, Valentí-Medina F, Bonfill-Ortí M, Martínez-Molina L. Necrobiosis lipoidica: a descriptive study of 35 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015 Jun;106(5):402-7.