Compression therapy is the mainstay of treatment for venous ulcers. In fact, it is very accurate to say that, “when faced with a venous ulcer, without compression there is no option for healing“.

However, there are times when, despite adequate compressive therapy, the evolution is not positive, since we do not manage to control the edema and/or the ulcer does not decrease in size. In this post we will analyze the situations that may be negatively affecting the wound and how to address them.

However, there are times when, despite adequate compressive therapy, the evolution is not positive, since we do not manage to control the edema and/or the ulcer does not decrease in size. In this post we will analyze the situations that may be negatively affecting the wound and how to address them.

1- The pressure exerted is not sufficient or is not adapted to the needs of the person and the wound.

This occurs mainly in the following cases:

The morphology of the leg is very altered by lipodermatosclerosis and obesity, so there is not an adequate pressure gradient between ankle and calf. In this situation we must pad the leg to homogenize the perimeters (See post: “Band and bandage: not the same thing“).

The location of the ulcer is retromalleolar and the bandage or stocking makes a “tent” effect in this location. Therefore we should use a pad for local pressure or bandage strips specifically for local pressure. Here is a recently published article on the experience with these strips in the retromalleolar region.

The frequency of bandage change is not sufficient to adapt to the pressure drop secondary to edema reduction. This tends to happen when we use short stretch bandages in people with high mobility and edema, because of their great effectiveness in the rapid decrease of edema. The solution is to increase the frequency of bandage change or to use multicomponent systems, with a cohesive elastic bandage, which favors the maintenance of the bandage in place.

2- Venous reflux control is not achieved.

In these cases, the Doppler ultrasound test will identify incompetent veins that require treatment, either surgical or endovenous. Endovenous treatments, such as sclerotherapy, are minimally invasive and their objective is to eliminate the reflux and, therefore, the cause of venous hypertension.

The echo-Doppler test will identify incompetent veins that require treatment. The benefit of sclerotherapy is not limited to ulcers with isolated superficial venous insufficiency. Its use in ulcers with an arterial component or with associated deep venous system involvement can help control venous hypertension, with a decrease in edema and with a direct impact on healing (see post: “Sclerotherapy wins against recurrence of venous leg ulcers“).

3- Continued sitting with the legs in decline

When the person’s habit is to spend most of the day sitting with the legs down, compression therapy is not enough to control venous hypertension. In fact, the hydrostatic pressure in the legs during sitting is almost as high as during standing, as this article shows. Therefore, venous ulcer patients (and everyone else, as a generalized recommendation) should elevate their legs when sitting. Other lifestyle changes such as a healthy diet, physical exercise and weight loss will also have a positive impact.

In fact, exercise is essential to activate the plantar and calf pump, and thus promote venous and lymphatic circulation. As we commented in the post “Band and bandage: it is not the same thing”, the higher the stiffness index of the compression system used, the more effective it will be in resisting muscle contraction and achieving high pressure peaks that create brief and intermittent venous occlusions, similar to physiological valvular functioning. As muscle contraction is so important, muscle atrophy or limited mobility may decrease the effectiveness of compression bandages.

In case of phlebolymphedema and immobility (wheelchair), if there is also some degree of arteriopathy (ITB>0.5), the bandage with a high stiffness index with pressures lower than 30 mmHg (or the Velcro-type closure wraps) is a safe and effective option if dorsiflexion and plantar flexion exercises are performed. (See post: “Phlebolymphedema: a term that should be more used“).

4- The wound is “superchronic”

The chronicity of the wound, i.e. a long time of evolution, also has a negative influence on the response to treatment.

Why is this so?

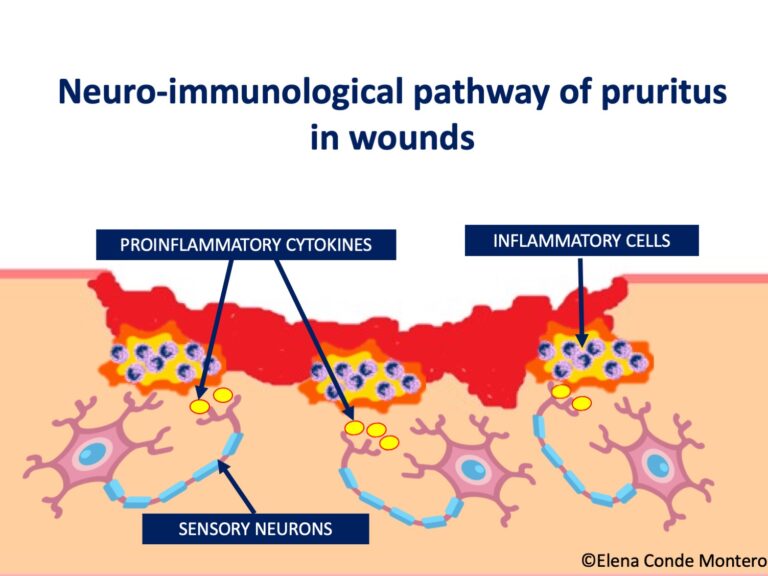

Whereas in an acute wound the cells divide rapidly, in a long-standing ulcer, the fibroblasts of the wound bed and the keratinocytes at the edges become senescent cells, i.e. cells that, due to proinflammatory signals maintained over time, stop dividing.

In addition, slougyh tissue that is chronically maintained in the wound is associated with an increased risk of resistant biofilms) and chronic wound edges tend to thicken and lichenify, which hinders epithelialization.

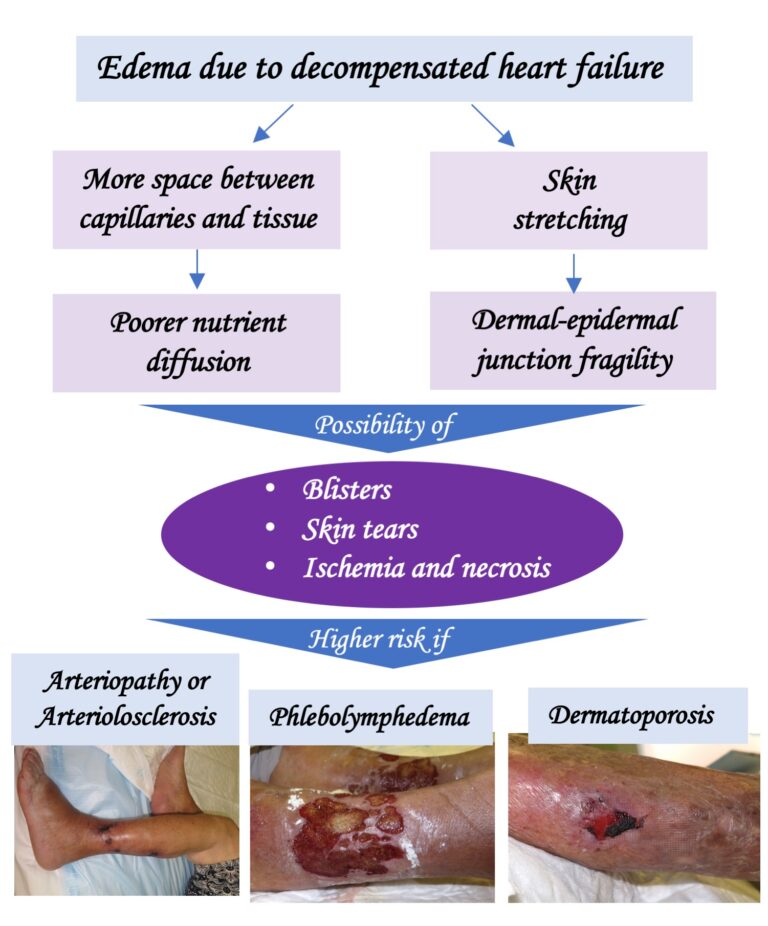

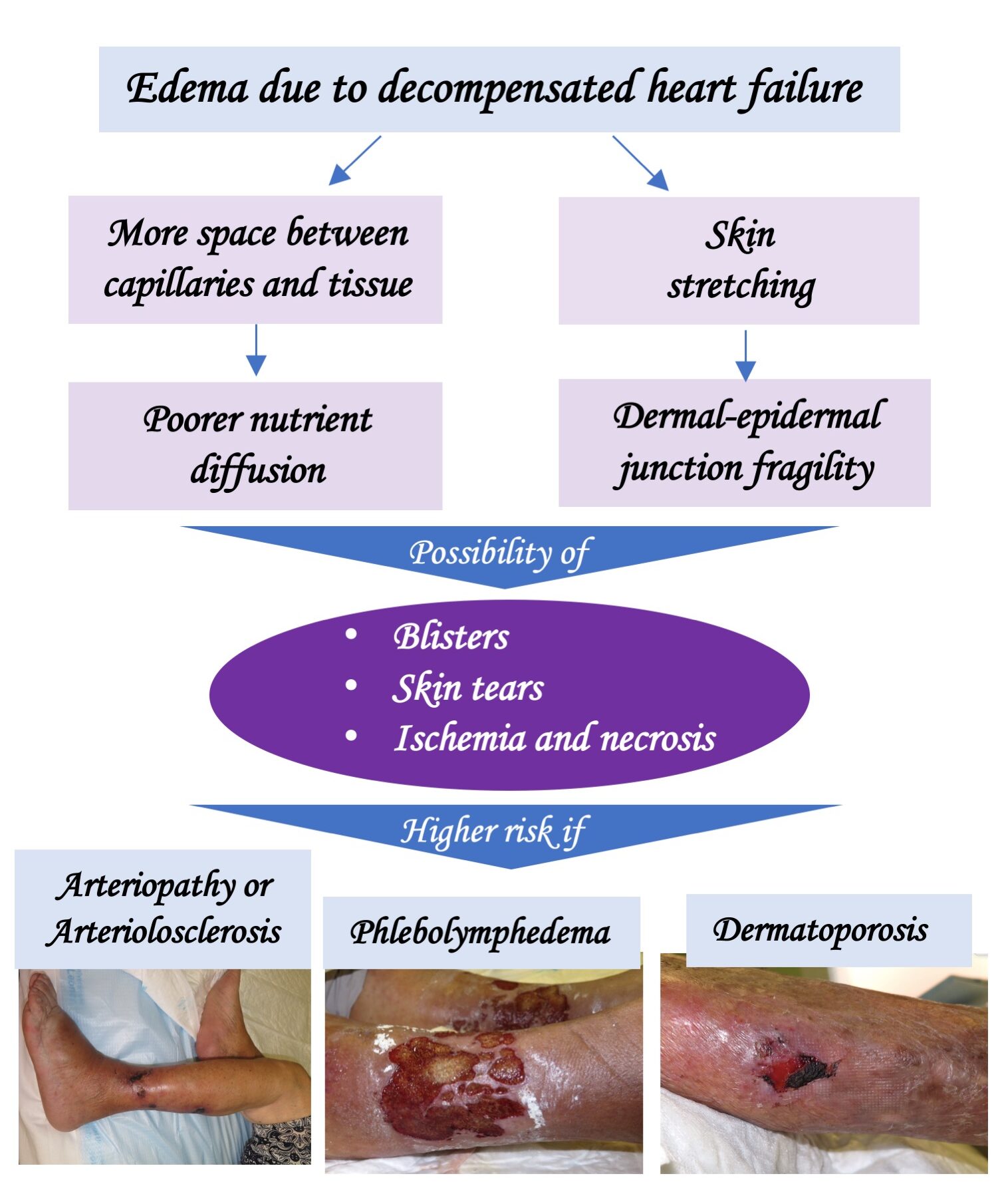

On the other hand, other factors that hinder healing are phlebolymphedema, the woody consistency of the perilesional skin due to lipodermatosclerosis, hemosiderin deposits that produce ochre dermatitis (see post: “Iron, ochre dermatitis and venous ulcer”) and dystrophic calcifications that can appear secondary to chronic inflammation (see post “Why do calcifications occur in chronic skin ulcers?“).

- So how can we help new tissue formation in these superchronic ulcers?

Sharp debridement and antimicrobial dressings will help fight biofilm.

In German-speaking countries, when lipodermatosclerosis is very intense, shave therapy is performed, which consists of excision of the ulcer and its inflammatory base in the hypodermis.

If there are dystrophic calcifications, their removal is essential to achieve wound closure.

Portable negative pressure therapy devices can stimulate granulation.

Skin grafts will promote epithelialization. Negative pressure therapy can facilitate graft attachment. Sometimes the procedure has to be repeated several times until complete epithelialization is achieved (See post: “Punch grafting and negative pressure therapy: a successful couple“).

5- Poor evolution is due to the occlusive effect of the dressings and bandage.

In cases where the problem is occlusion, the solution is to remove the dressings and bandages and leave the legs uncovered. To control edema in parallel, it is essential to rest with the legs elevated, ideally in bed with pillows under the legs.

This is not uncommon in wounds covered with punch grafts. In spite of adequate compression and rest with the legs elevated, sometimes in successive dressings during the first weeks we do not achieve complete epithelialization, with excessive exudate and a “congested” appearance of the grafts. Our experience is very good with the legs elevated and the application of zinc oxide drying solution once or twice a day on the grafted wound (See post: “In which situations would it be better to remove the bandage and leave the legs elevated and open air”).

6- When it is not a venous ulcer

The following statement is applicable to any wound: “If the response to a correct etiological treatment is not positive, you have to rethink the diagnosis of the wound”.

Look at the location, wound edges, wound bed tissue, perilesional skin… If you see atypical features that you would not expect to find in a venous ulcer, that person will benefit from dermatologic assessment and a skin biopsy… The differential diagnosis of venous ulcers is broad, and includes tumor ulcers (see post: “In front of a skin ulcer, when should we suspect a malignant ulcer?“).

In addition, it should be taken into account that, despite a predominantly venous ulcer, there may be some degree of associated arteriosclerosis (called mixed ulcer) or arteriolosclerosis (see post: “Little is said about arteriolosclerotic ulcers“).

This is an example of a wound treated for many years as a venous ulcer, with compression therapy, without improvement, because it was a basal cell carcinoma (note that hyperpigmented raised border;).

I hope this post has provided you with some tips to continue fighting the damn venous ulcer;)) I take this opportunity to encourage you to read this consensus document that we published in 2019 on the management of hard-to-heal wounds:):)

However, there are times when, despite adequate compressive therapy, the evolution is not positive, since we do not manage to control the edema and/or the ulcer does not decrease in size. In this post we will analyze the situations that may be negatively affecting the wound and how to address them.

However, there are times when, despite adequate compressive therapy, the evolution is not positive, since we do not manage to control the edema and/or the ulcer does not decrease in size. In this post we will analyze the situations that may be negatively affecting the wound and how to address them.