Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is the main ally of health professionals in this COVID-19 crisis. That is why it is so important that they are always available and that their manufacture and maintenance comply with established safety regulations. Although their very name implies that they protect, we also have to protect ourselves from them… We especially have to prevent them from damaging our skin. I have been wanting to write about this for a long time, but I needed more experience, both personal and from other health professionals, as well as research into what has been published on the subject. Since I’ll be taking part in a webinar on skin lesions secondary to PPEs on April 30th, organized by the EWMA (to which, of course, you’re all invited), I think it’s high time to dedicate a post to it in the blog.

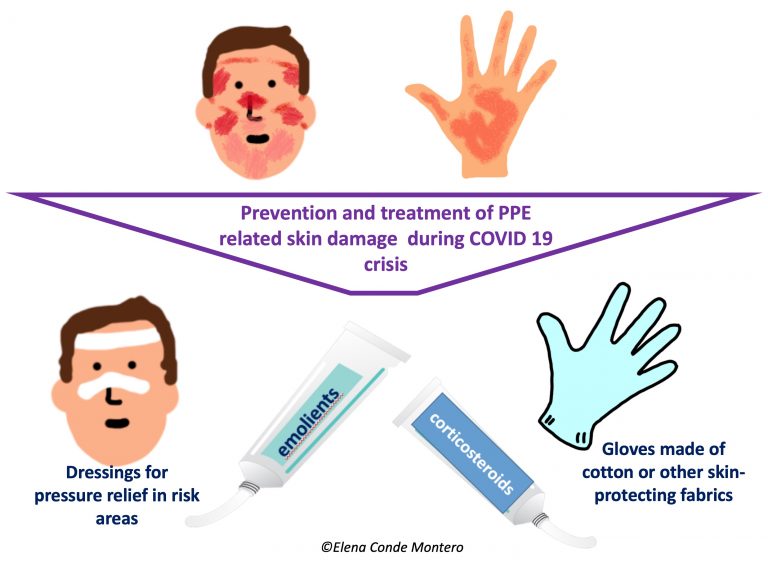

Knowing strategies for prevention and treatment of these injuries is essential, because when they appear they can be very limiting, with an impact on your quality of life and professional performance. Different scientific societies, hospitals and other health institutions are proposing and publishing recommendations and protocols for protection and treatment. Among others, I have found very interesting those of the British Society for Cutaneous Allergy & British Association of Dermatologists.

Before moving on to the injuries produced by protective goggles, masks and other devices that are part of this protective equipment, we have to deal with a problem that was already common among healthcare professionals, but which has increased exponentially in recent weeks: irritant hand dermatitis. This is due to excessive washing, the continuous use of hydro-alcoholic solutions and the prolonged use of several overlapping gloves, which alter the hydrolipidic layer of the skin and, therefore, cause the loss of the barrier function of the most superficial skin layer. People with chronic dermatitis, such as atopic dermatitis, are most affected. Although the degree and type of affectation is very variable (from dryness to fissures and erosions), and if there is any doubt or complication a dermatologist should evaluate you, there are a series of general measures that can be recommended:

- It is recommended that you pat your hands dry, not rub them.

- The application of unscented emollient products should be frequent, both in the hospital and at home. The use of paraffin products and coverage with cotton gloves or other skin protective fabrics is an interesting strategy during the hours of night rest to increase the penetration of the ointment and its moisturizing power.

- The “best emollient” is the one with which one feels hydrated and comfortable.

- If the application of moisturizing products is not enough and erythematous desquamative plaques, vesicles, lichenified lesions with fissures appear, it is important the dermatological evaluation since the use of topical corticosteroids of medium-high potency in cream or ointment during 1-2 weeks will help to control the outbreak. It should not be forgotten that, as in any case of irritant dermatitis, if its trigger cannot be eliminated (as it is in this case), the response to the treatment, or its duration, will be very variable.

We will now focus on the lesions produced specifically by the components of PPEs. A Chinese study on the prevalence of these injuries has just been published, in which 542 health professionals completed the surveys.1 The result was a prevalence of 97%. The most affected locations were the nasal bridge (most frequent, 83.1%), hands, cheeks and forehead. Dryness, tightness, scaling and erythema were the most common signs and symptoms. Another important result, which was to be expected, is that the risk of developing these lesions is greater in those professionals who are wearing the equipment (goggles, FFP2-FFP3 masks) for more hours. However, wearing face shield for more hours was not associated with more skin damage. This study also concludes that hand dermatitis is associated more with frequent washing than with prolonged use of gloves.1 The higher frequency of damage to the bridge of the nose is essentially explained by the pressure overlap of the goggles and mask.

Taking into account these findings described in the literature, which we also find in our daily practice in the hospital, here are some recommendations that may be useful:1-4

- Promotion, as far as possible, of short shifts among professionals (e.g. every 2 hours) to temporarily relieve the pressure zones of the FFP3 mask and avoid excess humidity under the mask.

- Use of fast-drying, residue-free barrier products that can prevent moisture damage (sweating) under the mask and other protective material.

- To alleviate pressure and friction in risk areas, mainly the nasal bridge, but also the forehead and cheeks, we can use different atraumatic dressings to act as an interface. Hydrocolloids and silicone foams are the most common. However, we have to make sure that their use does not prevent an adequate adaptation and sealing of glasses and mask to the face. In addition, we must take into account that frequent application and removal of these dressings can also cause damage to the epidermis, the most superficial layer of the skin.

- Taking into account that it is frequent the development of irritant contact dermatitis, with erythemato-descamative pruriginous lesions, it will be very important the facial moisturizing at home and, if necessary, the application of topical corticosteroid cream once a day during 3-4 days.

- The daily use of facial moisturizer is essential to protect the skin barrier. However, it is recommended that it be done at least 30 minutes before the application of the mask and other equipment to ensure its fixation and avoid altering its composition.

- Since it is frequent that those people with facial dermatitis, such as atopic dermatitis or seborrheic dermatitis, or acne, suffer some worsening of these pathologies, it is important that they maintain the treatment prescribed by the dermatologist for their outbreaks.

- Although the most frequent lesions are erythematous and oedematous macules and papules, which resolve themselves in hours (some erythemato-purpuric papules may persist for days), more or less superficial wounds (abrasions, erosions or ulcers) may appear, mainly in professionals who spend more time with PPEs. As these are acute and clean wounds, no protocol has shown superiority, but petroleum jelly in ointment, restorative creams with zinc, hyaluronic acid or different dressings could facilitate epithelialisation. However, like any wound, for successful treatment, an adequate etiological treatment must be performed. Therefore, equipment with other pressure points should be used. If this is not possible, maintaining the same pressure points will chronify the healing process .

Anything you want to contribute from your personal experience will greatly enrich this post 🙂

I would like to finish this post with a picture of the team I am proud of being part of these weeks, with which I share illusion and passion for giving the best of each one of us every day… But we are such a big team, that it would be very difficult to take a picture that would include all of us, ALL the professionals (without exception) that are working at the Hospital Virgen de la Torre… So I have preferred to finish with a song that I want to dedicate to all of them, to all of you: Toi+ moi

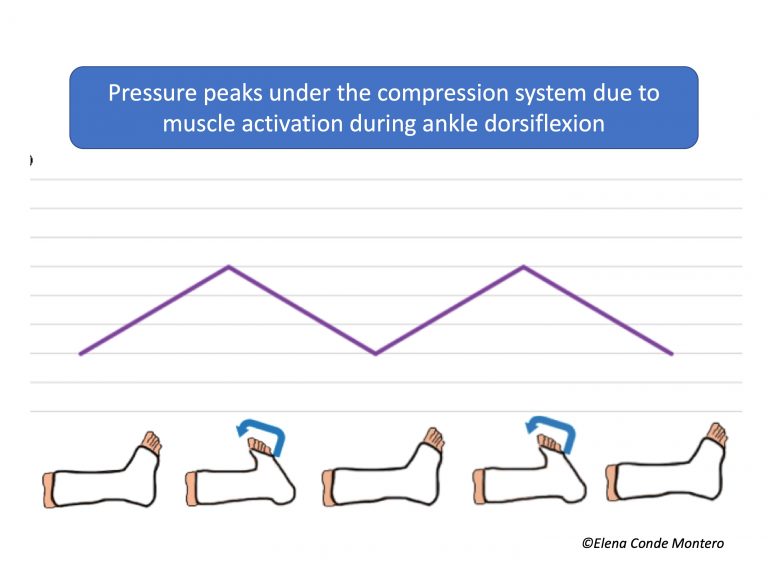

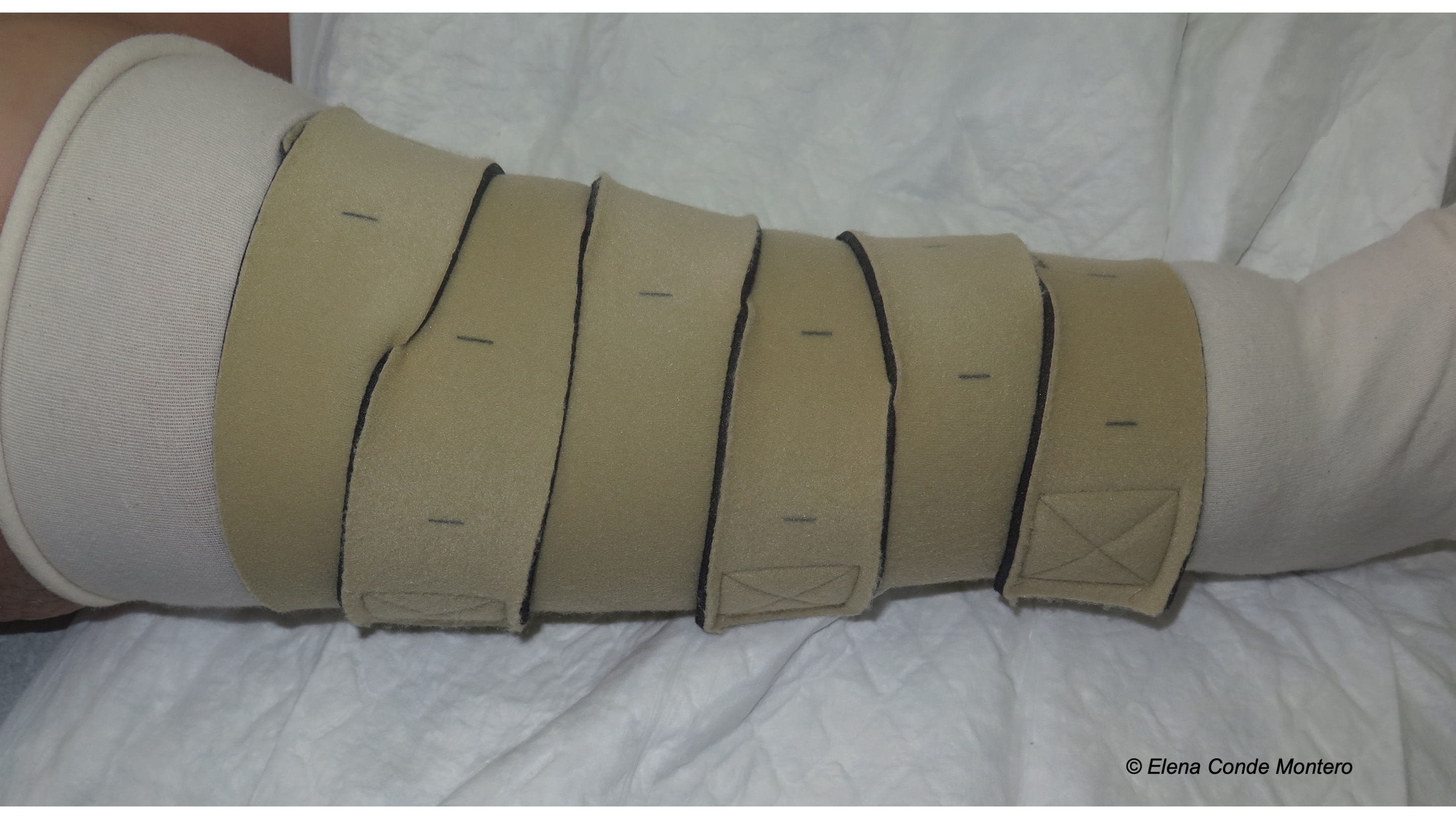

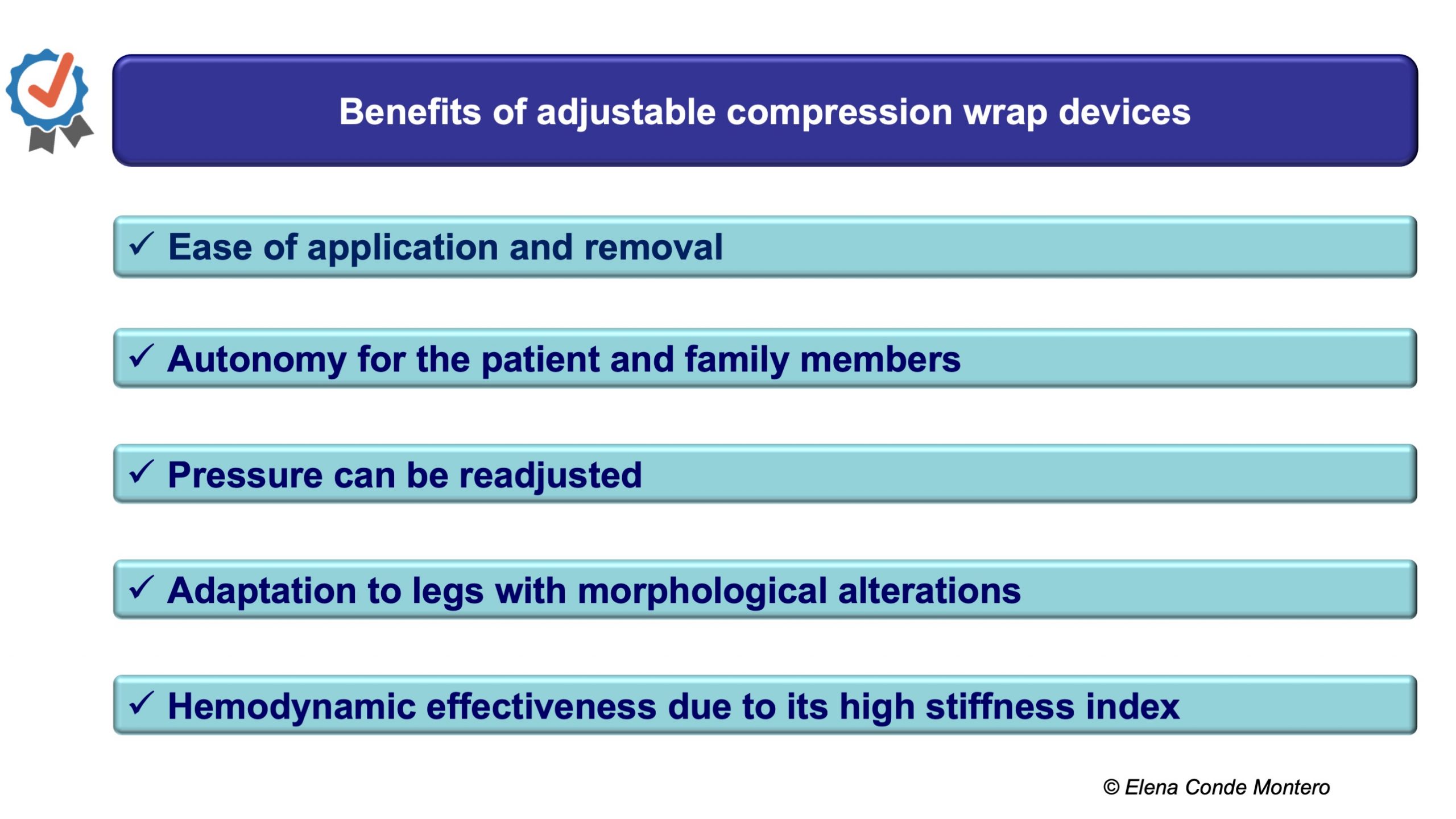

Venous hypertension was, without a doubt, the “protagonist” cause of the skin alterations I presented. In the post

Venous hypertension was, without a doubt, the “protagonist” cause of the skin alterations I presented. In the post