There’s a big news flash! A very relevant consensus document on compression therapy has just been published: Risks and contraindications of medical compression treatment – A critical reappraisal. An international consensus statement.

This is a critical review, up to November 2017, including 62 publications on adverse events associated with compression. With the data obtained, 15 SUPERexperts have agreed on 21 recommendations regarding contraindications to compression therapy and strategies to reduce the risk of adverse events.

Before moving to the recommendations, I would like to emphasize that, in this review, the adverse events most frequently associated with compression therapy are skin irritation, discomfort and pain. Exceptionally, severe injuries, such as nerve damage or soft tissue involvement, such as necrosis, have been reported.

How to prevent adverse events secondary to compression therapy?

Recommendation 1: “We recommend that every patient receiving compression therapy should be screened for conditions that increase the risk of complications, and every compression device should be checked for appropriate fit and application. Contraindications for compression treatment must be considered to limit the risk of side effects”.

How to control skin irritation and “marks” associated with compressive therapy?

Recommendation 2: “We recommend using adequate skin care to prevent skin irritation in patients with sensitive skin”.

The control of stasis eczema with corticoids and zinc oxide, use of emollients, adequate padding and the use of protective skin tissues directly on the skin under the compression devices are our best strategy in the clinical practice.

Although allergic reactions to materials used in compression devices are rare, how can they be avoided?

Recommendation 3: “To prevent allergic skin reactions due to compression devices, we suggest avoiding potentially allergenic substances and dyes in compression materials”.

How do you make compression therapy comfortable for the patient?

Recommendation 4: “In patients with discomfort and/or pain below compression garments, we recommend checking the correct indication, pressure level, material, fitting or bandage techniques as well as the correct donning and doffing”.

How to control the edema in the forefoot and toes?

Recommendation 5: “In patients with, or in those developing, forefoot or toe oedema when wearing compression, we suggest considering forefoot and toe bandaging or forefoot and toe compression pieces in addition to leg compression with a foot piece”.

Can I use compression in cases of local wound infection? What if the infection is systemic?

Recommendation 6: “In patients with bacterial or fungal infection beneath the compression device, we recommend considering treatment with topical antiseptics or topical antimicrobiological medication. In patients with systemic symptoms (fever, chills), erysipelas or cellulitis, we recommend that systemic treatment should be given. In other cases of systemic symptoms and severe local wound and tissue infection, the decision on the further treatment, including also medical compression, should be individualised on the basis of the local and general patient condition evaluation”.

Recommendation 7: “If the compression application or material is suspected to contribute to the infection (e.g. lateral pressure on toes with interdigital maceration), we suggest a modification of compression”.

For example, medical compression stocking with open toe or adjustable velcro devices.

How to avoid pressure injuries in risk areas?

Recommendation 8: “We suggest considering that, according to the Law of Laplace, the local pressure below the compression material may be higher than expected at bony and tendinous prominences such as above ankles, the tibia, the fibular head or above tendons such as the Achilles tendon, and to check those locations for skin lesions due to pressure”.

Recommendation 9: “To prevent tissue damage or necrosis and nerve damage in regions with a small radius, we suggest protecting these regions (tendons, nerves and bones) from inappropriate high pressure, particularly in patients with sensitive skin, by:

- Decreasing the local pressure by inserting soft padding material

- Using low overall pressure

- Taking appropriate circumference measurements so that the compression devices fit properly”.

Recommendation 10: “We suggest specific precaution (padding, special care of fit, low pressure), and close controls at the initial stages of compression therapy in patients with polyneuropathy and elderly patients with frail, atrophic skin (dermatoporosis)”.

How do you avoid causing nerve damage?

Recommendation 11: “We suggest considering that pressure-induced nerve damage may occur at specific points of the leg (e.g. fibular head) mainly in cases with excessive local compression pressure, e.g. due to ill-fitting medical compression stockings, thromboprophylactic stockings or compression bandages. Numbness and nerve palsy may occur. We suggest preventing high or continuous local pressure in regions with a risk of nerve compression as well as correct sizing and application of compression. Patients at higher risk for nerve damage (e.g. patients with diabetes, patients with neuropathy) should be treated with special caution to prevent nerve damage”.

When and how to apply compression therapy in a patient with artery disease?

Recommendation 12: “We recommend checking the arterial circulation status before any kind of compression therapy is initiated. If foot pulse and/or ankle pulse is weak or not palpable, ABPI should be measured and calculated prior to initiating medical compression therapy”.

Recommendation 13: “Severe PAOD (systolic ankle pressure <60 mmHg, toe pressure <30 mmHg) is a contraindication against compression therapy with medical compression stockings. In compression bandages, the applied pressure and the elasticity of the material are important. This contraindication does not apply to intermitent pneumatic compression and to patients with non-critical leg ischaemia treated with inelastic material applied with low resting pressure”.

Recommendation 14: “In every patient with impaired perfusion of the lower limb (ABI <0.9), the clinical effect of the medical compression stockings on leg blood supply should be carefully monitored. If the situation is not recognised, there is a possibility of developing non-healing skin breaks even under low pressure medical compression stockings”.

Can we apply compression therapy after bypass surgery?

Recommendation 15: “After bypass surgery with improved peripheral arterial pressures, medical compression treatment may be performed if there is no direct compression effect on the bypass itself. We suggest avoiding the compression of epifascial bypass conduits. As for all patients with chronic leg ischaemia, the recommendations regarding the use of medical compression treatment should be followed (see recommendations 12–14)”.

Is there a risk of venous thrombosis from poorly applied compression therapy?

Recommendation 16: “Because of a tourniquet effect, improper compression can cause local superficial venous thrombosis, especially in combination with prolonged sitting (long-haul flights). To prevent thromboembolic complications, we recommend avoiding a tourniquet effect and strangulation by inappropriate application of medical compression stockings, thromboprophylactic stockings and bandages”.

In case of cardiac insufficiency, what should I look out for?

Recommendation 17: “We recommend against applying compression in severe cases of cardiac insufficiency (NYHA IV). We also suggest against routine application of MCS in NYHA III cases. When needed, careful use of compression therapy in this patient group may be considered if there is a strict indication, with clinical and haemodynamic monitoring. In less severe cases, cautious increase of compression pressure only leads to very short phases of increased cardiac load and may lead to a substantial reduction of peripheral oedema”.

Is it appropriate to include compression in the treatment of superficial or deep vein thrombosis?

Recommendation 18: “We recommend considering that, in contrast to previous concepts, compression is not contraindicated in acute thrombotic events, but results in favourable clinical outcomes when applied with caution. In the hands of experts, proper compression leads to an immediate improvement of pain and oedema”.

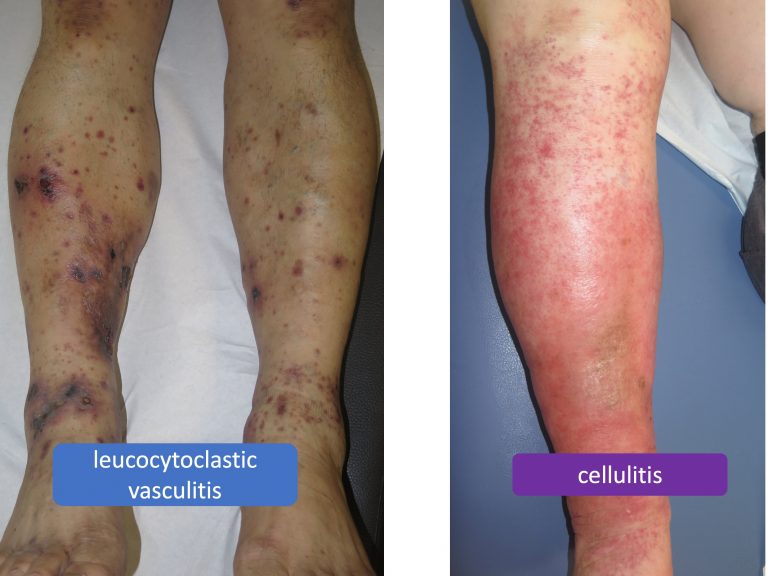

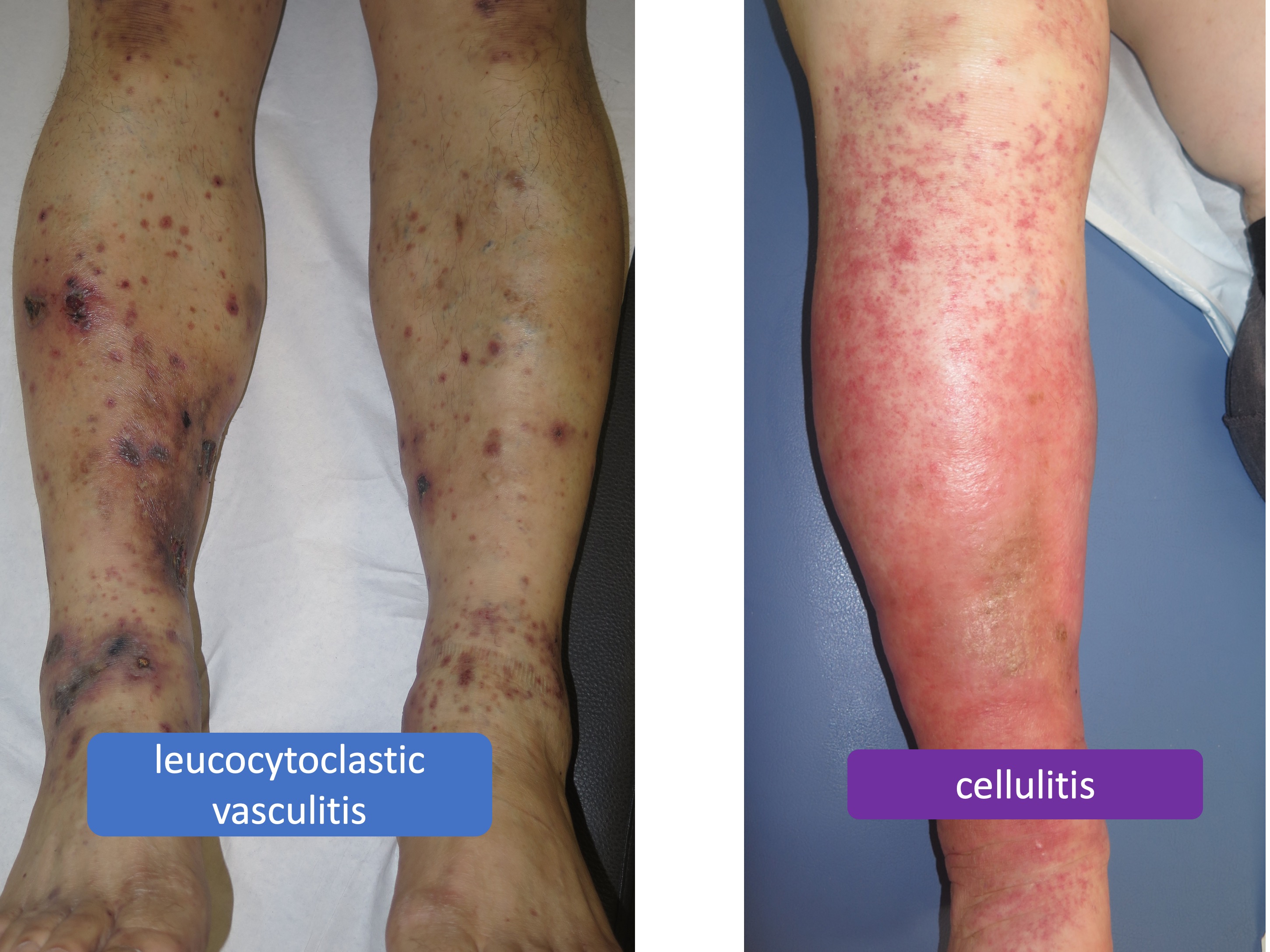

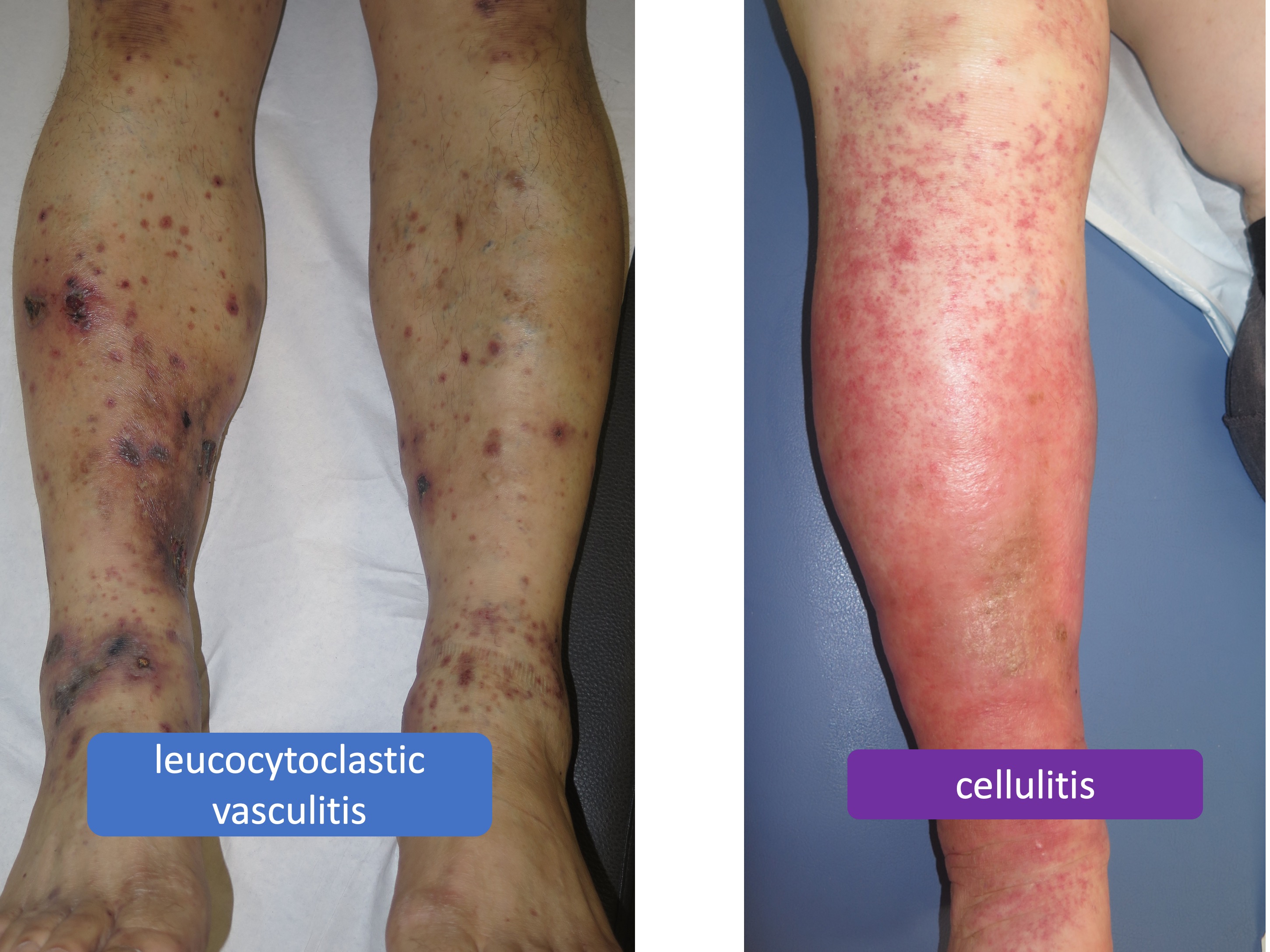

What are the benefits of compression in inflammatory diseases, such as vasculitis, or infectious diseases, such as cellulitis?

Recommendation 19: “We suggest additional compression, in purpura due to leucocytoclastic vasculitis and in leg erysipelas or cellulitis, to reduce inflammation, pain and oedema. In infectious inflammation, we suggest compression only in combination with antibacterial treatment.”

Recommendation 20: “Special precautions have to be taken if medical compression treatment is considered in patients with ‘borderline indications’. Treatment decisions should be taken on a case-by-case basis and under consideration of a careful benefit–risk assessment. In case of a favourable assessment, we suggest the use of low-pressure compression, the use of modified-compression strategies (compression materials) and the use of padding to reduce pressure peaks”.

So, for this group of SUPEREXPERTS what would be the absolute contraindications of compressive therapy?

Recommendation 21: “We recommend considering the following contraindications for sustained compression with thromboprophylactic stockings, adjustable compression wraps, medical compression stockings and elastic compression bandages:

- In patients with severe PAOD with any of the following: ABPI <0.6; ankle pressure <60 mmHg; toe pressure <30 mmHg; transcutaneous oxygen pressure < 20 mmHg

- Suspected compression of an existing epifascial arte- rial bypass

- Severe cardiac insufficiency (NYHA IV)

- Routine application of MC in NYHA III without strict indication, and clinical and haemodynamic monitoring

- Confirmed allergy to compression material

- Severe diabetic neuropathy with sensory loss or micro- angiopathy with the risk of skin necrosis (this may not apply to inelastic compression exerting low levels of sus- tained compression pressure (modified compression))”.

This means severe PAOD, compression of epifascial arterial bypasses, severe cardiac insufficiency and true allergy to compression material.