I think the title I have chosen sums up perfectly the situation of this type of wound: it is much more frequent ulcer than we think, but it is underdiagnosed and we do not usually call it by its name.

As the EWMA has just organized a Masterclass in which I have talked about this topic, it is the perfect time to dedicate a post to these ulcers secondary to small vessel disease.

What is cutaneous arteriolosclerosis?

It is defined as a thickening of the wall of the arterioles of the deep dermis and subcutaneous cellular tissue. The term “cutaneous arteriolosclerosis” includes different entities in the literature: proliferative and hyaline arteriolosclerosis, which is ubiquitously found in untreated hypertension, and fibrosing endarteritis and medial calcinosis of Mönckeberg, linked to aging. Therefore, arteriolosclerosis can be found in legs of any elderly or hypertensive person, it is not specific to patients with wounds.1

What is the clinical presentation of arteriolosclerotic ulcers?

These are very painful leg ulcers, with signs of necrosis, erythematous-violaceous borders, which can progress rapidly. Since this description could fit perfectly with arterial ulcers, the first thing to do when exploring an ulcer with these characteristics is pulse palpation. People with arteriolosclerotic ulcers will always have palpable pulses.

What is the difference between arteriolosclerotic ulcer and Martorell ulcer?

There is no difference. In fact, when talking about arteriolosclerotic ulcer, the first thing that comes to mind is Martorell ulcer. The so-called hypertensive ischemic Martorell ulcer is a lesion secondary to subcutaneous arteriolosclerosis (see post: “Key elements to understanding Martorell ulcer”).

But in the clinical-histopathological spectrum of Martorell ulcer, and therefore of ulcers due to arteriolosclerosis, there is also, on the one hand, calciphylaxis, as we commented in the post “Martorell ulcer and vitamin K antagonists: a dangerous combination” and, on the other hand, ulcers due to age-associated arteriolopathy (See post “Large leg wounds after mild trauma”). In fact, while the history of chronic renal insufficiency is a differentiating factor for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, there is no particularly distinguishing feature between ulcers due to age-related arteriolopathy and the ulcer known as Martorell ulcer.

There are fewer and fewer deaths due to major cardiovascular events, so we are more frequently encountering minor cardiovascular events, such as ulcers due to arteriolosclerosis. In fact, with the increased control of diabetes and hypertension, the clinical and histologic presentation of arteriolosclerosis ulcers in most cases is not as striking as in the early descriptions of Martorell ulcer in the literature.

We will perform a biopsy of the edge of the lesion in case we want to rule out other etiologies (See post: “Necrosis and violaceous edges in leg ulcers: keys to guide its diagnosis“).

What is the treatment?

The management of ulcers due to arteriolosclerosis is the same as that discussed in other posts on Martorell ulcer and ulcers due to arteriolopathy associated with age (See post: “How to close large ulcers after minor trauma in the elderly”).

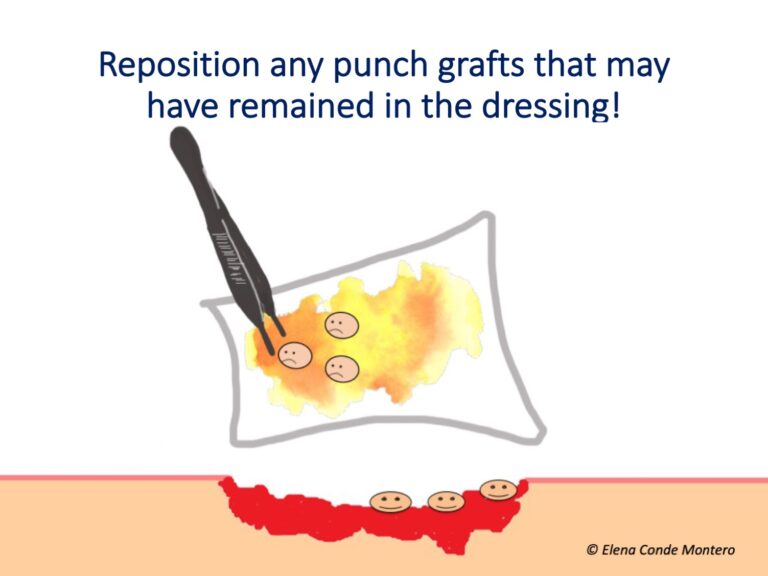

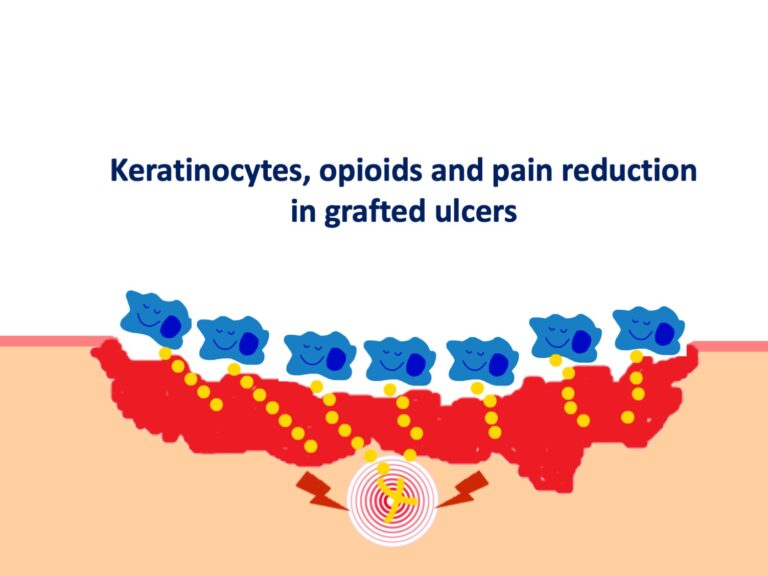

In addition to the control of risk factors such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension, it is essential to control pain, stop necrosis and promote epithelialization. For this, in our practice we use sequential punch grafting, with or without negative pressure therapy, with excellent response.2 Sevoflurane irrigation is another alternative strategy that can help control pain and promote vasodilatation in the wound bed. (See post: “Have you ever heard of the use of topical sevoflurane in wounds?“)

I recommend you the posts: “How to close large ulcers after mild trauma in the elderly?” , “Interest of early punch grafting in Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer” and “Punch grafting as a painkiller for painful ulcers”.

Can compressive therapy be used?

Yes, of course! Always adapted to the needs of each person

In these patients, as the pain is extreme and constant, there is a decrease in calf muscle pumping due to a significant reduction in gait (patients stop walking to avoid pain), leading to edema and decreased skin perfusion. This edema may also explain why pain increases in these patients when standing. Therefore, compression will increase perfusion by reducing edema and improve pain. In addition, its use will enhance graft attachment (see post “Compression is key to treating leg wounds”).

Ideally, compression devices with a high stiffness index (short stretch bandages or multicomponent bandages) should be used to obtain a low resting pressure, and pressure peaks during walking. The level of compression depends on the patient’s tolerance, but 20-30 mmHg may be sufficient (see post: “What type of compression therapy to choose in each situation“).

References:

- Monfort JB, Cury K, Moguelet P, Chasset F, Bachmeyer C, Francès C, Barbaud A, Senet P. Cutaneous Arteriolosclerosis Is Not Specific to Ischemic Hypertensive Leg Ulcers. Dermatology. 2018;234(5-6):194-197.

- Conde-Montero E, Pérez Jerónimo L, Peral Vázquez A, Recarte Marín L, Sanabria Villarpando PE, de la Cueva Dobao P. Early and Sequential Punch Grafting in the Spectrum of Arteriolopathy Ulcers in the Elderly. Wounds. 2020 Aug;32(8):E38-E41.

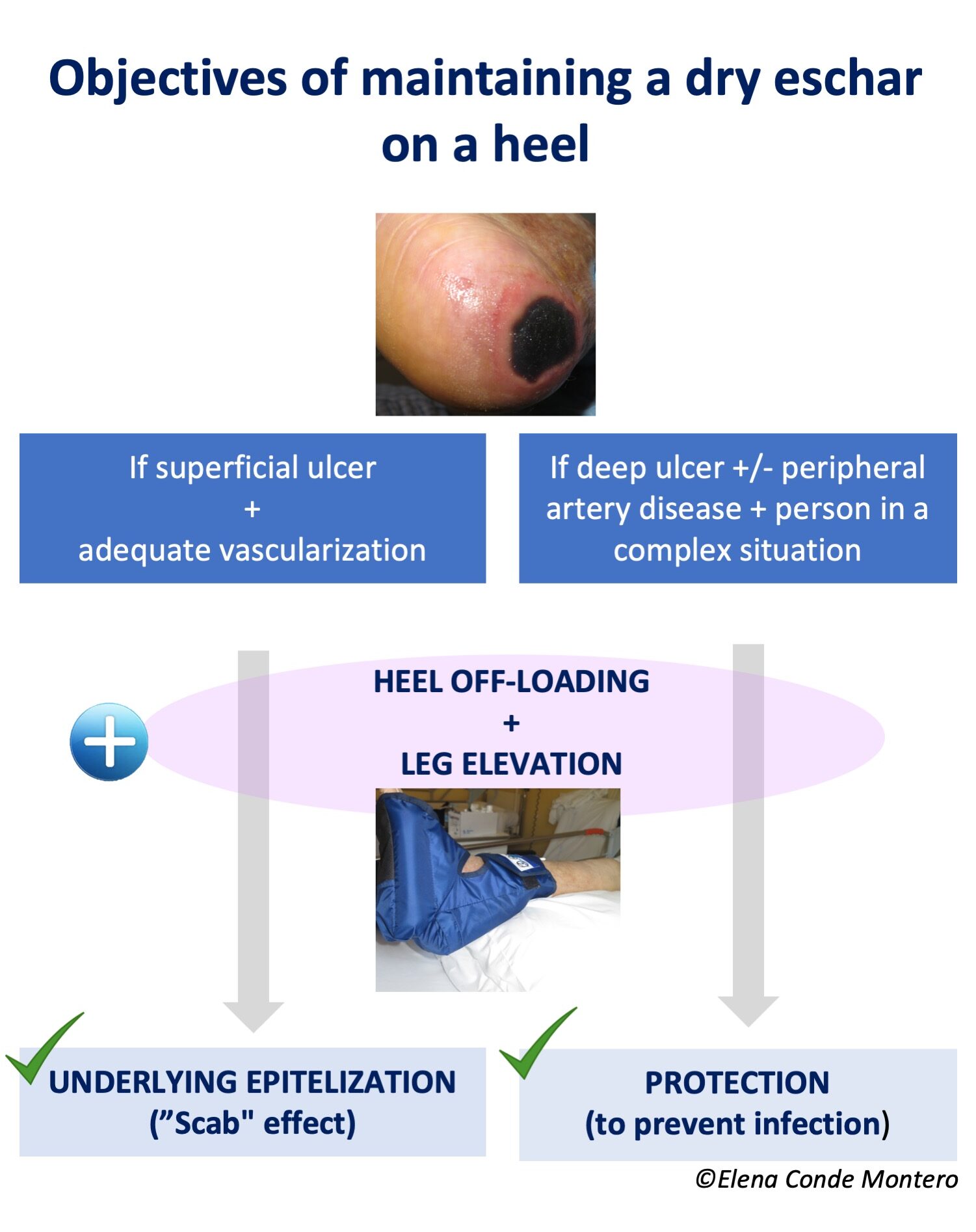

This photo shows a case of

This photo shows a case of