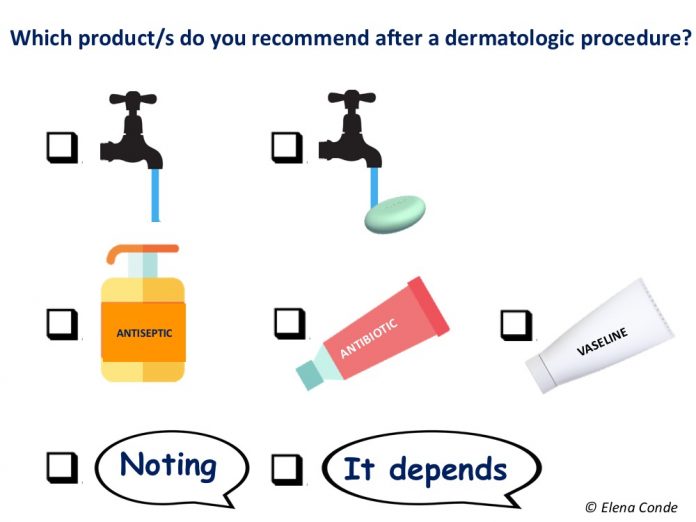

The unnecessary use of topical antibiotics in clean acute wounds is an issue I spoke about 4 years ago in the post “How do we manage clean wounds secondary to dermatological procedures?” I have been encouraged to write about it again after reading an interesting article recently published in the journal Dermatologic Surgery: “Variability in wound care recomendations following dermatologic procedures”.

The authors of this article perform a search on the recommendations after interventional procedures (biopsies, extirpations, curettage, cryotherapy, electrocoagulation, among others) that different dermatological centers have available on the Internet for patients. They analyse 169 protocols, mainly from US centres. 65% of them recommend the use of several topical products, which can cause doubts to the patient when choosing which one to use (and if there is an antibiotic in the list it is not difficult for the patient to think that this is the best option). Among the recommendations of the majority of protocols (84%) is the application of petrolatum-based products. However, it is striking that almost half of them (43%) propose the use of topical antibiotics, when the scientific evidence tells us that these drugs are not indicated in the management of these clean acute wounds. In addition to not representing a benefit to prevent infection or to accelerate healing in comparison with petrolatum- based products, their use can be related to bacterial resistance, development of allergic contact eczema and toxicity in fibroblasts and keratinocytes. In other words, not only do they not produce benefit, but they can also trigger complications that slow healing. In fact, certain topical antibiotics, such as neomycin, top the list of major allergens associated with allergic contact dermatitis.

Considering that there is no universally standardized protocol for the treatment of these post-surgical wounds, we should not be surprised by the heterogeneity of the recommendations found in this study. In fact, the same search carried out in Spanish would also show a great variability between centres and a widespread use of topical antibiotics.

But the problem of the absence of agreed and standardized treatment guidelines is not limited to wounds after dermatological procedures, but to clean acute wounds in general. While there are multiple clinical guidelines and consensus documents for the treatment of chronic wounds, documents with evidence-based recommendations for the management of acute wounds are scarce. In this context, a multidisciplinary group of wound experts from the Netherlands reviewed the available evidence and published in 2015 a guideline on the management of acute wounds (Ubbink 2015). In the absence of scientific evidence on any point, the authors of the paper reflect their opinion as experts. I like the practical and concise approach of these guidelines, the recommendations of which coincide for the most part with the daily clinical practice of our practice. Among others, we find the following recommendations, to which I add in italics my personal opinion:

- Sutured wounds in aseptic conditions, as occurs in dermatological procedures such as biopsies and larger or smaller removals, do not require cleansing and the use of antiseptics, as the available evidence does not show that these measures reduce infection rates.

- If we leave a wound open for closure by secondary intention, recommendations will vary depending on the size and thickness of the wound. Superficial or small sized wounds would not need any coverage. As I commented in the post “Compressive therapy after dermatological surgery on the leg“, if no contraindication exists, as in any leg wound, therapeutic compression, adapted to the patient’s tolerance, helps to reduce inflammation to accelerate the healing of the lesions in this location.

- If the wound is closed and dry, covering it does not reduce the risk of infection and dressing changes can be painful. In addition, in sebaceous areas, such as the nose, occlusion or the use of petrolatum-based products can produce excess moisture, and consequent inflammation, with the possibility of delayed healing. In the case of mild exudate, the patient can use a conventional gauze dressing to absorb it and avoid friction with clothing. If the exudate is greater, a more absorbent dressing should be selected. No dressing has shown superiority over others. One type of wound that we let close by secondary intention is the graft donor site. As I commented in the post “What dressing should I choose to cover the graft donor site?” there are different options to adapt to the needs of the patient and the wound. The dressing that we use most in acute wounds is alginate, because of its hemostatic and absorbent power and its capacity to form “pseudo-physiological” scabs (see post “Why do we use so many alginate fibre sheets in our wound clinic?”).

- Although it is a recommendation that we usually make in all cases, cleansing of acute wounds is also a controversial issue, since, as we saw in the post “The art of wound cleansing“, it does not seem to be associated with a lower rate of infection or other benefits in healing. In fact, the authors of this paper only recommend cleansing dirty wounds with warm tap water by gentle irrigation. Isn’t physiological scabbing the best coverage for a clean wound to heal?

With all this we have just commented on, it seems clear that we should not recommend mupirocin ointment to a patient after curettage and electrocoagulation of a skin lesion. However, is it better to recommend wound cleansing with soap and water and vaseline every day or not to do any treatment? Is it better to apply vaseline or a repair cream with hyaluronic acid or zinc (see posts “Reasons for the hyaluronic acid boom in wound healing“, “Why do we use topical zinc in wounds and perilesional skin“)? What a dilemma… We need comparative studies that allow us to identify the best wound care protocol for clean acute wounds.

What is clear is that for these patients we must recommend sun protection during several months to reduce the risk of developing hyperpigmentation in the treated area.

In addition, since we know that a wound that does not close or causes pathological scarring (hypertrophy or keloid) is characterized by an abnormally prolonged inflammatory phase, the patient must avoid anything that may prolong that inflammatory phase. Therefore, other recommendations such as quitting smoking or avoiding activities that may produce tension at the edges of the wound will also facilitate healing.

After these dermatological procedures, the patient must receive clear instructions on what to do and what not to do, must be informed of possible complications that may appear, such as infection, and must ask any questions that arise. It is important for the patient to know that any healing process involves the presence of an inflammatory phase, the signs of which can sometimes be confused with those of infection. Well-informed patients have more control over their health and, consequently, their health will improve!