As we commented in the post “Brief overview of wound healing”, regardless of their cause, all chronic ulcers share a common characteristic: an abnormally prolonged inflammatory phase. In this pro-inflammatory microenvironment, it is constant the presence of greater activity of enzymes that destroy the extracellular matrix and prevent the action of growth factors. These proteins are called metalloproteinases and have become a promising target for the development of new bioactive dressings.

Why is there so much interest in the use of metalloproteinase modulating dressings? The following points will help you understand this.

What are matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)?

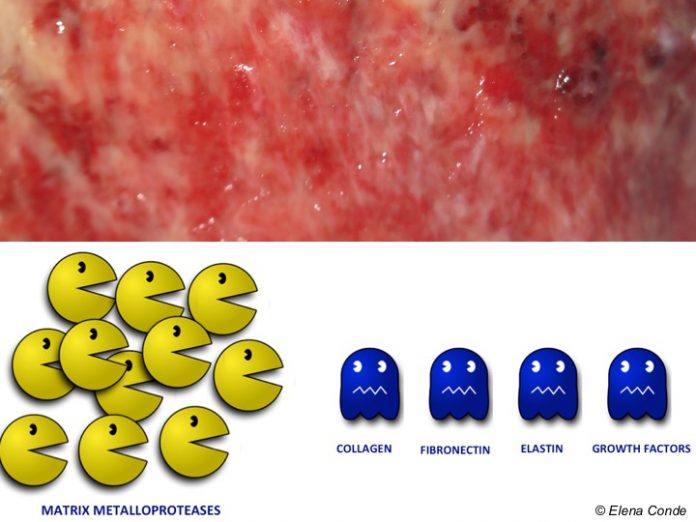

They are a family of enzymes with the same function: the destruction of extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen or proteoglycans.

Twenty-three types have been described. Of these, the most identified and studied in wounds are MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-8 and MMP-9.

MMPs intervene in all phases of the normal healing process and are produced by:

- Inflammatory cells (neutrophils and macrophages)

- Wound tissue cells (epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells)

| Phases of the healing process | Action of MMPs |

| Inflammation |

|

| Proliferation |

|

| Remodelling |

|

They are excreted inactive (in the form of pro-MMP). In order to exert their proteolytic action, they have to be activated by other proteases. Their inactivation depends on tissue enzymes called TIMPs (Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases). The most relevant aspect is the MMPs/ TIMPs ratio.

Why are MMPs so important in chronic skin ulcers?

Unlike in acute wounds, which heal properly, in chronic ulcers MMPs remain at high levels for a long time, destroying proteins essential for healing (growth factors, collagen, fibronectin). In these recalcitrant wounds TIMPs also decrease, so the MMPs/TIMPs ratio increases, with a dangerously positive proteolytic balance. High concentrations of MMPs correlate with low wound healing rates.

Biofilms that are generated collaborate in this proteolytic activity. On the one hand, bacteria organize themselves forming adherent matrices in which they secrete cytotoxic molecules and bacterial proteases. On the other hand, given that this type of organization makes bacteria more resistant, the number of inflammatory cells in the wound increases. These macrophages and leukocytes release more cytokines, free radicals and, therefore, the production of proteases is stimulated. This response, which is ineffective and produces a vicious cycle, prevents the regeneration of an adequate extracellular matrix.

How may we stop their activity?

The activity of metalloproteinases may be reduced by different mechanisms:

- Removal of proteases from the wound bed through absorbent dressings (exudate is a liquid that is rich in proteases), sharp debridement or negative pressure therapy.

- Molecules prepared to bind to MMPs, inactivate them and, consequently, reduce protease activity. Different products are on the market with this function, such as collagen and oxygenated regenerated cellulose dressings or nano-oligosaccharide factorlipido-colloid matrix.

- Inhibition of MMP synthesis by means of dressings impregnated with polyhydrated ionogens.

- The use of antimicrobial products, which reduce the bacterial load in wounds, may help to reduce the proteolytic environment in the wound.

My experience with metalloproteinase modulating dressings is very good. However, since the load or activity of MMPS is not a parameter that we can measure in daily clinical practice, and these dressings are normally used in combination with other treatments, such as sharp debridement and compression therapy in venous leg ulcers, it is difficult to determine the clinical impact of the specific action of these products on metalloproteinases.

I recommend the following review: MMPs Made Easy